26 Oct Leaders who coach: Building belief and backbone

The practice (or as some would say: the ‘art of’) coaching has existed in different guises for centuries. In sport, coaches are critical to the development of sporting teams and elite athletes. In a health setting, professional coaching referred to as ‘supervised reflective practice’ is a mandatory requirement for maintaining credentials in a range of medical and allied health professions. Within the corporate sector, professional coaches typically work with leaders and the organisation’s ‘future talent’ to facilitate their development, optimise performance and activate succession plans at individual, team and executive levels.

Over the past three decades, I have witnessed a significant shift in thinking towards a greater understanding and investment in sponsoring executive coaching activities in organisations. Senior leaders consistently rank coaching as the most powerful vehicle to develop their interpersonal, team leadership, self-management and influencing capabilities. Interest in recruiting and developing talent who demonstrate a strong appetite for applying coaching skills and mindsets to engage key stakeholders has also grown exponentially. Yet despite the best of intentions and a genuine belief in the value of coaching to unleash potential, coaching is far from being embedded in the fabric of leadership practice. Whether leading in the private, public sector or not-for-profit organisations, leaders are under relentless competitive market pressure; to meet ever-tightening governance and regulatory demands; to deliver tangible, measurable impact and to navigate a host of complex, unprecedented challenges and ‘wicked problems’. Striving to survive, let alone thrive in our ‘Covid-normal’ world, leaders are now, more than ever, focusing on getting the job done and executing quick wins. Engaging in what are assumed to be lengthy coaching conversations with peers, stakeholders and teams are viewed as a time and energy-consuming luxury.

We understand what drives this thinking and the resultant, very natural, human responses to stress and threat. Lazarus and Folkman’s well-researched model of psychological stress reveals that when we cognitively assess the demands of our life and work circumstances as outweighing the resources that we typically call on to feel psychologically safe, we feel emotionally activated.

![]()

Under sustained pressure and sensing threats to psychological safety, leaders default to well-worn, habitual patterns of behaviour that tend to show up at either end of the leadership spectrum. Autocratic (‘do it my way or hit the highway’) leadership practices can appear overtly in the form of labelling, blaming or attacking. Less overt, yet just as harmful signs of this form of control manifest through speaking way more than listening. At the other extreme, Laissez-Faire (‘hands off’) styles of leadership tend to abdicate responsibilities for facilitating collaborative dialogue through self-protective mechanisms of masking, complying, minimising or avoiding opportunities to engage in shared meaning-making.

Another layer of complexity emerging more recently in Covid times relates to the growing realisation that accountability can co-exist with freedom. Engaged workforces will continue to work remotely, even with 80% vaccination rates. In preparing to meaningfully engage with peers and teams in virtual and hybrid work environments, leaders are faced with having to navigate multiple agendas without the richer, sensory ‘in-the-room’ data taken for granted in pre-Covid times.

As a result, coaching takes up little airtime in the multitude of meetings and ‘check-in’ conversations held within the workplace. This can mean that leaders and staff at all levels of an organisation are unclear about what is expected of them, are unlikely to feel valued or deeply trusted and might feel untethered and ungrounded. Over time, team members stop bringing forth new ways of thinking, as they know that their ideas will be shunned or overlooked, resulting in lower levels of commitment, greater stress, inconsistent performance, stronger turnover intentions and in the extreme – tangible resistance to change imperatives.

The aim of this article is to explore the relevance of coaching to you and your organisation. You might reflect on the kind of leadership behaviours that are expected and modelled in your workplace and consider the extent to which coaching is, or could be, having a significant impact on engagement, wellbeing and organisational success.

What is Coaching?

I notice that the concepts of ‘coaching’ and ‘mentoring’ are often used interchangeably in organisations. In my experience, mentoring is more about securing the support and wise counsel from a more experienced person (either from within or external to the workplace). The mentor typically shares their storehouse of insights, helping an individual prepare for their next job role and providing advocacy, guidance and validation.

The role of a coach is one of a catalyst; to provide a psychologically safe, reflective thinking space that piques insight, supports meaning-making, challenges assumptions and ignites action through exploration and inquiry.

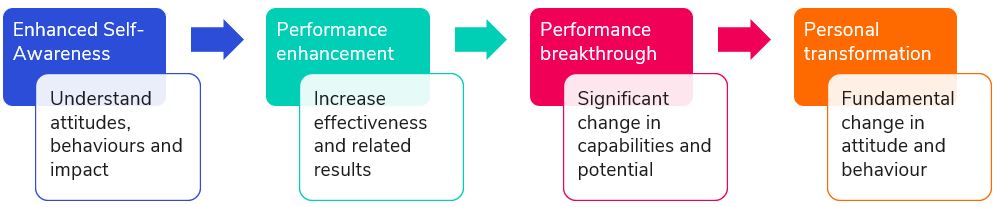

Coach and coachee partner to set the purpose of the coaching conversation. As the focus shifts, achieving mutually agreed goals will have increasing levels of impact:

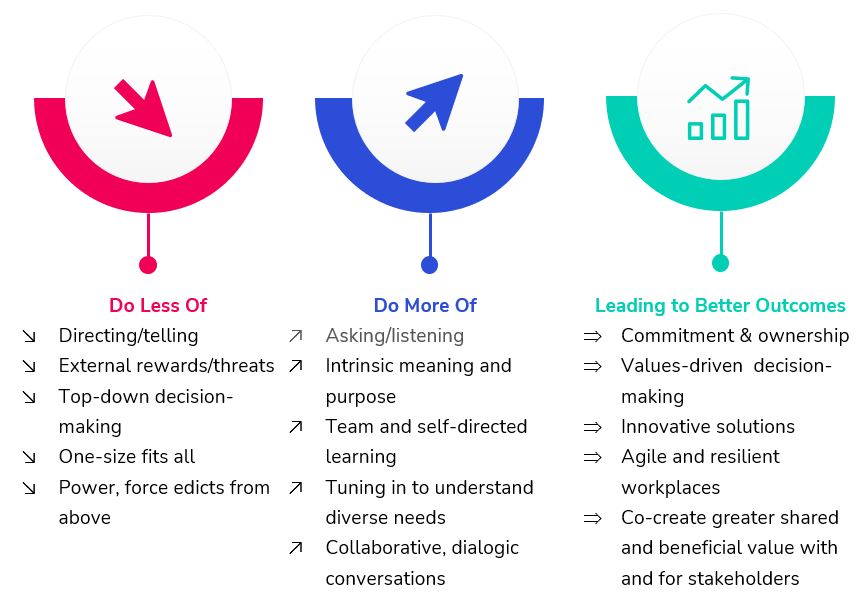

Clearly, successfully leading organisational change, particularly in a dynamic, ever-shifting context, requires those leaders with the most influence to recognise how they personally impact the culture of the workplace. Leadership impact is a consequence of the organisation’s culture that sets expectations for leadership behaviour, which in turn, reinforces culture. So together, both elements have a significant impact on performance, engagement and the ability of the organisation to achieve its vision and purpose.

In my experience, exceptional leaders are those who recognise that coaching is a non-negotiable aspect of their leadership practice; a way of thinking and crucially, a set of capabilities that model curiosity, collaboration, diversity of thinking, empowered problem solving and a strong message of unconditional support. They strategically and practically apply coaching behaviours in a range of stakeholder relationships to reinforce expectations (often quite subtle and implicit) that strongly influence how people interact with each other and approach their work.

In fact, displaying belief and backbone in coaching in an organisational setting means that all members, unrestricted by reporting relationships, perceived status differences or diverse perspectives, feel psychologically safe enough to courageously engage in coaching conversations. In this context, people consider the relevance of their roles and their capacity to meaningfully contribute to their future and so are more likely to embrace the difficulties, uncertainties, and disappointments that growth and change entail.

The use of coaching by leaders with peers, customers, stakeholders and team members is a powerful and highly effective mechanism to gently, yet firmly challenge assumptions and optimise personal and team accountability, engagement and resilience.

Coaching shifts the culture of the workplace:

Research findings from peer-reviewed coaching psychology journals in Australia, UK and USA have shown that workplace coaching results in increased levels of self-awareness and self-efficacy, more open communication, greater job satisfaction, perceptions of equality, flexibility, higher performance, ownership, effective succession plans and career sustenance. Leaders who coach generate cultures infused with stress management resources, enhanced goal striving, positive well-being outcomes, hope and self-confidence (Gyllensten & Palmer, 2006; Kauffman & Scoular, 2004; Seligman, 2002).

For example, the majority of managers in one explorative study observed improved ability to deal with issues, more effective solutions to problems, heightened confidence in surfacing conflict and greater clarity on personal goals (Leonard-Cross 2010). Analyses of 3600 feedback results from within corporations and government departments in the U.S. revealed strongly significant correlations between leaders’ coaching effectiveness (as perceived by their peers, their boss and their direct reports/ team members) and measures of employee commitment and engagement of their people. In fact, coaching effectiveness was found to be more than double the likelihood that people wouldn’t consider leaving their employer as they considered their current environment the preferable ‘greener pasture’.

Where to start?

Build belief and backbone into your culture so that it becomes a way of life in your organisation. To start, you could:

- Set clear expectations (through executive recruitment, talent management and succession planning processes) that coaching behaviours are critical elements of a leader’s role.

- Harvest success stories for how coaching has made a difference – encouraging leaders to tell personal stories that illustrate the importance and impact of coaching.

- Promote and profile those leaders who coach well – effectively reinforcing positive consequences for prioritising coaching conversations as a key component of their roles.

- Provide leaders with a regular, safe space to test out and gain helpful feedback on their coaching skills with peers who can help each other normalise experiences, develop trust and build strong, productive and sustainable relationships.

- Consider instituting ‘peer coaching’ processes that go far beyond initial coach training to foster trust, collaboration and mutual support as being at the heart of the coaching partnership.

- Make it easy for leaders to get help when they need it through offering coaching from their own managers/executive members/ peers and/or professional coaches so they have ‘lived experience’ in being coached and can draw on these conversations when coaching others.

- Recognise that the greatest changes will be observed ‘on the job’ (between coaching conversations) so helping people become more reflective about their daily interactions and attempting new behaviours in the course of their regular schedule becomes an important area of focus for leaders and the organisation at large.

One of the most compelling, albeit challenging aspects of a leader’s development journey, in my view, is the opportunity to deeply connect with self, others and one’s constantly shifting and multiple life and work contexts. As a leader, being open to experimenting with innovative and practical ways to facilitate informal coaching conversations at every opportunity will engage in ways that are emotionally resonant and meaningful to each person. This might mean developing confidence and capability to coach not only your team members, peers and stakeholders, but your own ‘inner village’. As you learn to recognise and manage the interplay between relational, personal and systemic threats, you will no doubt find a greater sense of ease in navigating the often complex and ever-changing landscape of work.

Your vision will become clear only when you look into your heart … Who looks outside, dreams. Who looks inside, awakens. —Carl Jung

Written by Kerryn Miller

Director of Coaching,

Organisational Psychologist at PiqueGlobal,

Co-Chair at Association for Coaching (Victoria).